Chapter 2 Page tables¶

Page tables are the mechanism through which the operating system controls whatmemory addresses mean. They allow xv6 to multiplex the address spaces of differentprocesses onto a single physical memory, and to protect the memories of different processes. The level of indirection provided by page tables is also a source for many neattricks. xv6 uses page tables primarily to multiplex address spaces and to protect memory. It also uses a few simple pagetable tricks: mapping the same memory (the kernel) in several address spaces, mapping the same memory more than once in one address space (each user page is also mapped into the kernel’s physical view of memory),and guarding a user stack with an unmapped page. The rest of this chapter explainsthe page tables that the x86 hardware provides and how xv6 uses them.

Paging hardware¶

As a reminder, x86 instructions (both user and kernel) manipulate virtual addresses.The machine’s RAM, or physical memory, is indexed with physical addresses. The x86page table hardware connects these two kinds of addresses, by mapping each virtualaddress to a physical address.

An x86 page table is logically an array of 2^20 (1,048,576) page table entries(PTEs). Each PTE contains a 20-bit physical page number (PPN) and some flags. Thepaging hardware translates a virtual address by using its top 20 bits to index into thepage table to find a PTE, and replacing the address’s top 20 bits with the PPN in thePTE. The paging hardware copies the low 12 bits unchanged from the virtual to thetranslated physical address. Thus a page table gives the operating system control overvirtual-to-physical address translations at the granularity of aligned chunks of 4096(2^12) bytes. Such a chunk is called a page.

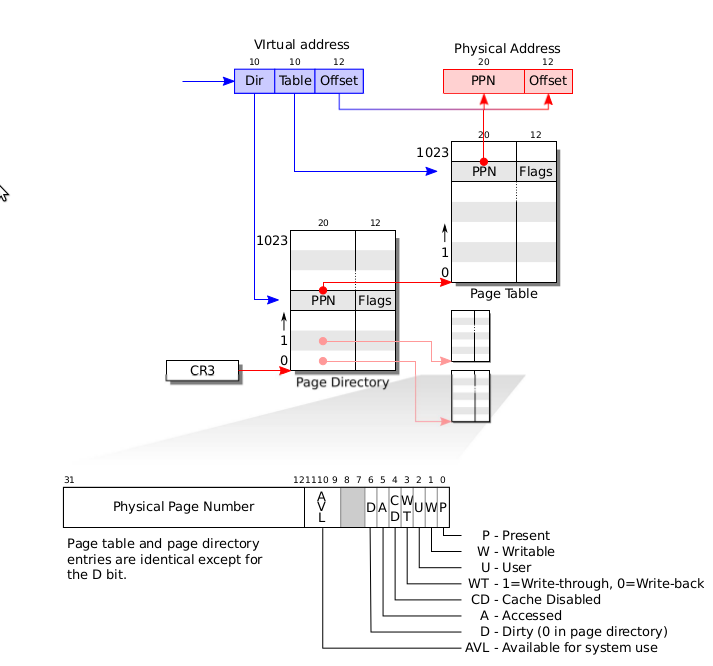

As shown in Figure 2-1, the actual translation happens in two steps. A page tableis stored in physical memory as a two-level tree. The root of the tree is a 4096-bytepage directory that contains 1024 PTE-like references to page table pages. Eachpage table page is an array of 1024 32-bit PTEs. The paging hardware uses the top 10bits of a virtual address to select a page directory entry. If the page directory entry ispresent, the paging hardware uses the next 10 bits of the virtual address to select aPTE from the page table page that the page directory entry refers to. If either thepage directory entry or the PTE is not present, the paging hardware raises a fault.This two-level structure allows a page table to omit entire page table pages in the common case in which large ranges of virtual addresses have no mappings.

Each PTE contains flag bits that tell the paging hardware how the associated virtual address is allowed to be used. PTE_P indicates whether the PTE is present: if it isnot set, a reference to the page causes a fault (i.e. is not allowed). PTE_W controls

Figure 2-1. x86 page table hardware.

whether instructions are allowed to issue writes to the page; if not set, only reads andinstruction fetches are allowed. PTE_U controls whether user programs are allowed touse the page; if clear, only the kernel is allowed to use the page. Figure 2-1 shows howit all works. The flags and all other page hardware related structures are defined inmmu.h (0200).

A few notes about terms. Physical memory refers to storage cells in DRAM. Abyte of physical memory has an address, called a physical address. Instructions useonly virtual addresses, which the paging hardware translates to physical addresses, andthen sends to the DRAM hardware to read or write storage. At this level of discussionthere is no such thing as virtual memory, only virtual addresses.

Process address space¶

The page table created by entry has enough mappings to allow the kernel’s Ccode to start running. However, main immediately changes to a new page table bycalling kvmalloc (1757), because kernel has a more elaborate plan for describing process address spaces.

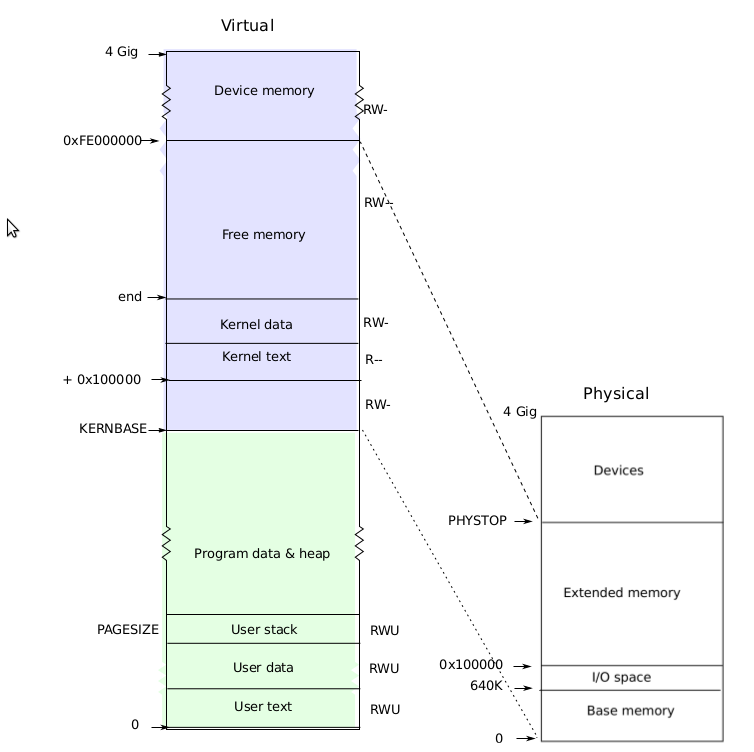

Each process has a separate page table, and xv6 tells the page table hardware toswitch page tables when xv6 switches between processes. As shown in Figure 2-2, aprocess’s user memory starts at virtual address zero and can grow up to KERNBASE, allowing a process to address up to 2 GB of memory. When a process asks xv6 formore memory, xv6 first finds free physical pages to provide the storage, and then adds PTEs to the process’s page table that point to the new physical pages. xv6 sets thePTE_U, PTE_W, and PTE_P flags in these PTEs. Most processes do not use the entireuser address space; xv6 leaves PTE_P clear in unused PTEs. Different processes’ pagetables translate user addresses to different pages of physical memory, so that each process has private user memory.

Figure 2-2. Layout of a virtual address space and the physical address space.

Xv6 includes all mappings needed for the kernel to run in every process’s page table; these mappings all appear above KERNBASE. It maps virtual addresses KERNBASE:KERNBASE+PHYSTOP to 0:PHYSTOP. One reason for this mapping is so that thekernel can use its own instructions and data. Another reason is that the kernel sometimes needs to be able to write a given page of physical memory, for example whencreating page table pages; having every physical page appear at a predictable virtualaddress makes this convenient. A defect of this arrangement is that xv6 cannot makeuse of more than 2 GB of physical memory. Some devices that use memorymappedI/O appear at physical addresses starting at 0xFE000000, so xv6 page tables includinga direct mapping for them. Xv6 does not set the PTE_U flag in the PTEs above KERNBASE, so only the kernel can use them.

Having every process’s page table contain mappings for both user memory andthe entire kernel is convenient when switching from user code to kernel code duringsystem calls and interrupts: such switches do not require page table switches. For the most part the kernel does not have its own page table; it is almost always borrowingsome process’s page table.

To review, xv6 ensures that each process can only use its own memory, and thateach process sees its memory as having contiguous virtual addresses starting at zero.xv6 implements the first by setting the PTE_U bit only on PTEs of virtual addressesthat refer to the process’s own memory. It implements the second using the ability ofpage tables to translate successive virtual addresses to whatever physical pages happento be allocated to the process.

Code: creating an address space¶

main calls kvmalloc (1757) to create and switch to a page table with the mappingsabove KERNBASE required for the kernel to run. Most of the work happens in setup-kvm (1737). It first allocates a page of memory to hold the page directory. Then it calls mappages to install the translations that the kernel needs, which are described in thekmap (1728) array. The translations include the kernel’s instructions and data, physicalmemory up to PHYSTOP, and memory ranges which are actually I/O devices. setup-kvm does not install any mappings for the user memory; this will happen later.

mappages (1679) installs mappings into a page table for a range of virtual addressesto a corresponding range of physical addresses. It does this separately for each virtualaddress in the range, at page intervals. For each virtual address to be mapped, mappages calls walkpgdir to find the address of the PTE for that address. It then initializes the PTE to hold the relevant physical page number, the desired permissions (PTE_W and/or PTE_U), and PTE_P to mark the PTE as valid (1691).

walkpgdir (1654) mimics the actions of the x86 paging hardware as it looks upthe PTE for a virtual address (see Figure 2-1). walkpgdir uses the upper 10 bits ofthe virtual address to find the page directory entry (1659). If the page directory entryisn’t present, then the required page table page hasn’t yet been allocated; if the allocargument is set, walkpgdir allocates it and puts its physical address in the page directory. Finally it uses the next 10 bits of the virtual address to find the address of thePTE in the page table page (1672).

Physical memory allocation¶

The kernel needs to allocate and free physical memory at run-time for page tables, process user memory, kernel stacks, and pipe buffers.

xv6 uses the physical memory between the end of the kernel and PHYSTOP forrun-time allocation. It allocates and frees whole 4096-byte pages at a time. It keepstrack of which pages are free by threading a linked list through the pages themselves.Allocation consists of removing a page from the linked list; freeing consists of addingthe freed page to the list.

There is a bootstrap problem: all of physical memory must be mapped in orderfor the allocator to initialize the free list, but creating a page table with those mappingsinvolves allocating page-table pages. xv6 solves this problem by using a separate pageallocator during entry, which allocates memory just after the end of the kernel’s data segment. This allocator does not support freeing and is limited by the 4 MB mappingin the entrypgdir, but that is sufficient to allocate the first kernel page table.

Code: Physical memory allocator¶

The allocator’s data structure is a free list of physical memory pages that are available for allocation. Each free page’s list element is a struct run (2764). Where doesthe allocator get the memory to hold that data structure? It store each free page’s runstructure in the free page itself, since there’s nothing else stored there. The free list isprotected by a spin lock (2764-2766). The list and the lock are wrapped in a struct tomake clear that the lock protects the fields in the struct. For now, ignore the lock andthe calls to acquire and release; Chapter 4 will examine locking in detail.

The function main calls kinit1 and kinit2 to initialize the allocator (2780). Thereason for having two calls is that for much of main one cannot use locks or memoryabove 4 megabytes. The call to kinit1 sets up for lock-less allocation in the first 4megabytes, and the call to kinit2 enables locking and arranges for more memory tobe allocatable. main ought to determine how much physical memory is available, butthis turns out to be difficult on the x86. Instead it assumes that the machine has 240megabytes (PHYSTOP) of physical memory, and uses all the memory between the endof the kernel and PHYSTOP as the initial pool of free memory. kinit1 and kinit2 callfreerange to add memory to the free list via per-page calls to kfree. A PTE can onlyrefer to a physical address that is aligned on a 4096-byte boundary (is a multiple of4096), so freerange uses PGROUNDUP to ensure that it frees only aligned physical addresses. The allocator starts with no memory; these calls to kfree give it some tomanage.

The allocator refers to physical pages by their virtual addresses as mapped in highmemory, not by their physical addresses, which is why kinit uses p2v(PHYSTOP) totranslate PHYSTOP (a physical address) to a virtual address. The allocator sometimestreats addresses as integers in order to perform arithmetic on them (e.g., traversing allpages in kinit), and sometimes uses addresses as pointers to read and write memory(e.g., manipulating the run structure stored in each page); this dual use of addresses isthe main reason that the allocator code is full of C type casts. The other reason isthat freeing and allocation inherently change the type of the memory.

The function kfree (2815) begins by setting every byte in the memory being freedto the value 1. This will cause code that uses memory after freeing it (uses ‘‘danglingreferences’’) to read garbage instead of the old valid contents; hopefully that will causesuch code to break faster. Then kfree casts v to a pointer to struct run, records theold start of the free list in r->next, and sets the free list equal to r. kalloc removesand returns the first element in the free list.

User part of an address space¶

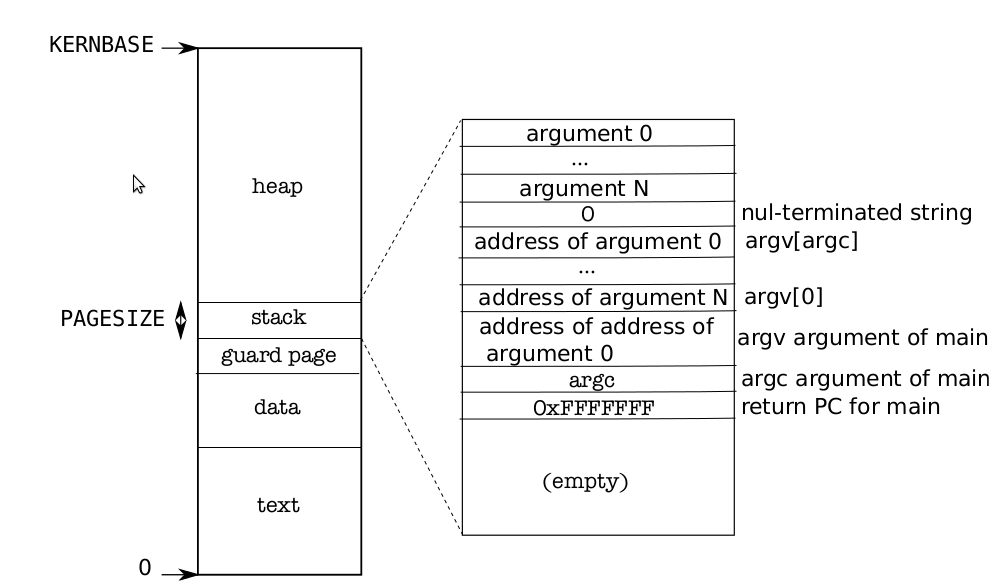

Figure 2-3 shows the layout of the user memory of an executing process in xv6.The heap is above the stack so that it can expand (with sbrk). The stack is a singlepage, and is shown with the initial contents as created by exec. Strings containing the command-line arguments, as well as an array of pointers to them, are at the very topof the stack. Just under that are values that allow a program to start at main as if thefunction call main(argc, argv) had just started. To guard a stack growing off thestack page, xv6 places a guard page right below the stack. The guard page is notmapped and so if the stack runs off the stack page, the hardware will generate an exception because it cannot translate the faulting address.

Figure 2-3. Memory layout of a user process with its initial stack.

Code: exec¶

Exec is the system call that creates the user part of an address space. It initializes theuser part of an address space from a file stored in the file system. Exec (5910) opensthe named binary path using namei (5920), which is explained in Chapter 6. Then, itreads the ELF header. Xv6 applications are described in the widely-used ELF format,defined in elf.h. An ELF binary consists of an ELF header, struct elfhdr (0955), followed by a sequence of program section headers, struct proghdr (0974). Each progh-dr describes a section of the application that must be loaded into memory; xv6 programs have only one program section header, but other systems might have separatesections for instructions and data.

The first step is a quick check that the file probably contains an ELF binary. AnELF binary starts with the four-byte ‘‘magic number’’ 0x7F, ’E’, ’L’, ’F’, orELF_MAGIC (0952). If the ELF header has the right magic number, exec assumes thatthe binary is well-formed.

Exec allocates a new page table with no user mappings with setupkvm (5931), allocates memory for each ELF segment with allocuvm (5943), and loads each segment into memory with loaduvm (5945). allocuvm checks that the virtual addresses requested isbelow KERNBASE. loaduvm (1818) uses walkpgdir to find the physical address of the allocated memory at which to write each page of the ELF segment, and readi to readfrom the file.

The program section header for /init, the first user program created with exec,looks like this:

# objdump -p _init

_init: file format elf32-i386

Program Header:

LOAD off 0x00000054 vaddr 0x00000000 paddr 0x00000000 align 2**2

filesz 0x000008c0 memsz 0x000008cc flags rwx

The program section header’s filesz may be less than the memsz, indicating thatthe gap between them should be filled with zeroes (for C global variables) rather thanread from the file. For /init, filesz is 2240 bytes and memsz is 2252 bytes, and thusallocuvm allocates enough physical memory to hold 2252 bytes, but reads only 2240bytes from the file /init.

Now exec allocates and initializes the user stack. It allocates just one stack page.Exec copies the argument strings to the top of the stack one at a time, recording thepointers to them in ustack. It places a null pointer at the end of what will be theargv list passed to main. The first three entries in ustack are the fake return PC,argc, and argv pointer.

Exec places an inaccessible page just below the stack page, so that programs thattry to use more than one page will fault. This inaccessible page also allows exec todeal with arguments that are too large; in that situation, the copyout function that exec uses to copy arguments to the stack will notice that the destination page in not accessible, and will return –1.

During the preparation of the new memory image, if exec detects an error likean invalid program segment, it jumps to the label bad, frees the new image, and returns –1. Exec must wait to free the old image until it is sure that the system call willsucceed: if the old image is gone, the system call cannot return –1 to it. The only error cases in exec happen during the creation of the image. Once the image is complete, exec can install the new image (5989) and free the old one (5990). Finally, execreturns 0.

Real world¶

Like most operating systems, xv6 uses the paging hardware for memory protection and mapping. Most operating systems make far more sophisticated use of pagingthan xv6; for example, xv6 lacks demand paging from disk, copy-on-write fork, sharedmemory, lazily-allocated pages, and automatically extending stacks. The x86 supportsaddress translation using segmentation (see Appendix B), but xv6 uses segments onlyfor the common trick of implementing per-cpu variables such as proc that are at afixed address but have different values on different CPUs (see seginit). Implementations of per-CPU (or per-thread) storage on non-segment architectures would dedicatea register to holding a pointer to the per-CPU data area, but the x86 has so few general registers that the extra effort required to use segmentation is worthwhile.

On machines with lots of memory it might make sense to use the x86’s 4 Mbyte‘‘super pages.’’ Small pages make sense when physical memory is small, to allow allocation and page-out to disk with fine granularity. For example, if a program uses only8 Kbyte of memory, giving it a 4 Mbyte physical page is wasteful. Larger pages makesense on machines with lots of RAM, and may reduce overhead for page-table manipulation. Xv6 uses super pages in one place: the initial page table (1311). The array initialization sets two of the 1024 PDEs, at indices zero and 960 (KERNBASE>>PDXSHIFT),leaving the other PDEs zero. Xv6 sets the PTE_PS bit in these two PDEs to mark themas super pages. The kernel also tells the paging hardware to allow super pages by setting the CR_PSE bit (Page Size Extension) in %cr4.

Xv6 should determine the actual RAM configuration, instead of assuming 240MB. On the x86, there are at least three common algorithms: the first is to probe thephysical address space looking for regions that behave like memory, preserving the values written to them; the second is to read the number of kilobytes of memory out of aknown 16-bit location in the PC’s non-volatile RAM; and the third is to look in BIOSmemory for a memory layout table left as part of the multiprocessor tables. Readingthe memory layout table is complicated.

Memory allocation was a hot topic a long time ago, the basic problems being efficient use of limited memory and preparing for unknown future requests; see Knuth.Today people care more about speed than space-efficiency. In addition, a more elaborate kernel would likely allocate many different sizes of small blocks, rather than (as inxv6) just 4096-byte blocks; a real kernel allocator would need to handle small allocations as well as large ones.

Exercises¶

- Look at real operating systems to see how they size memory.

- If xv6 had not used super pages, what would be the right declaration for entrypgdir?

- Unix implementations of exec traditionally include special handling for shell scripts.If the file to execute begins with the text #!, then the first line is taken to be a program to run to interpret the file. For example, if exec is called to run myprog arg1and myprog’s first line is #!/interp, then exec runs /interp with command line/interp myprog arg1. Implement support for this convention in xv6.