Chapter 4 Locking¶

Xv6 runs on multiprocessors, computers with multiple CPUs executing code independently. These multiple CPUs operate on a single physical address space and sharedata structures; xv6 must introduce a coordination mechanism to keep them from interfering with each other. Even on a uniprocessor, xv6 must use some mechanism tokeep interrupt handlers from interfering with non-interrupt code. Xv6 uses the samelow-level concept for both: a lock. A lock provides mutual exclusion, ensuring thatonly one CPU at a time can hold the lock. If xv6 only accesses a data structure whileholding a particular lock, then xv6 can be sure that only one CPU at a time is accessing the data structure. In this situation, we say that the lock protects the data structure.

The rest of this chapter explains why xv6 needs locks, how xv6 implements them,and how it uses them. A key observation will be that if you look at a line of code inxv6, you must be asking yourself is there another processor that could change the intended behavior of the line (e.g., because another processor is also executing that lineor another line of code that modifies a shared variable) and what would happen if aninterrupt handler ran. In both case you have to keep in mind that each line of C canbe several machine instructions and thus another processor or an interrupt may mockaround in the middle of a C instruction. You cannot assume that lines of code on thepage are executed sequentially, nor can you assume that a single C instruction will execute atomically. Concurrency makes reasoning about the correctness much more difficult.

Race conditions¶

As an example on why we need locks, consider several processors sharing a singledisk, such as the IDE disk in xv6. The disk driver maintains a linked list of the outstanding disk requests (3821) and processors may add new requests to the list concurrently (3954). If there were no concurrent requests, you might implement the linked list as follows:

1 struct list {

2 int data;

3 struct list *next;

4 };

5

6 struct list *list = 0;

7

8 void

9 insert(int data)

10 {

11 struct list *l;

12

13 l = malloc(sizeof *l);

14 l->data = data;

15 l->next = list;

16 list = l;

17 }

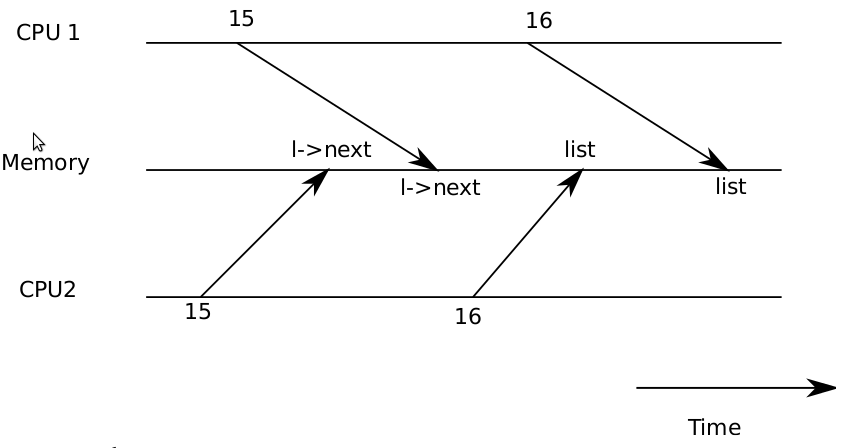

Figure 4-1. Example race

Proving this implementation correct is a typical exercise in a data structures and algorithms class. Even though this implementation can be proved correct, it isn’t, at leastnot on a multiprocessor. If two different CPUs execute insert at the same time, itcould happen that both execute line 15 before either executes 16 (see Figure 4-1). Ifthis happens, there will now be two list nodes with next set to the former value oflist. When the two assignments to list happen at line 16, the second one will overwrite the first; the node involved in the first assignment will be lost. This kind ofproblem is called a race condition. The problem with races is that they depend onthe exact timing of the two CPUs involved and how their memory operations are ordered by the memory system, and are consequently difficult to reproduce. For example, adding print statements while debugging insert might change the timing of theexecution enough to make the race disappear.

The typical way to avoid races is to use a lock. Locks ensure mutual exclusion, sothat only one CPU can execute insert at a time; this makes the scenario above impossible. The correctly locked version of the above code adds just a few lines (notnumbered):

6 struct list *list = 0;

struct lock listlock;

7

8 void

9 insert(int data)

10 {

11 struct list *l;

12

acquire(&listlock);

13 l = malloc(sizeof *l);

14 l->data = data;

15 l->next = list;

16 list = l;

release(&listlock);

17 }

When we say that a lock protects data, we really mean that the lock protects somecollection of invariants that apply to the data. Invariants are properties of data structures that are maintained across operations. Typically, an operation’s correct behaviordepends on the invariants being true when the operation begins. The operation maytemporarily violate the invariants but must reestablish them before finishing. For example, in the linked list case, the invariant is that list points at the first node in thelist and that each node’s next field points at the next node. The implementation ofinsert violates this invariant temporarily: line 13 creates a new list element l with theintent that l be the first node in the list, but l’s next pointer does not point at thenext node in the list yet (reestablished at line 15) and list does not point at l yet(reestablished at line 16). The race condition we examined above happened because asecond CPU executed code that depended on the list invariants while they were (temporarily) violated. Proper use of a lock ensures that only one CPU at a time can operate on the data structure, so that no CPU will execute a data structure operation whenthe data structure’s invariants do not hold.

Code: Locks¶

Xv6’s represents a lock as a struct spinlock (1401). The critical field in the structureis locked, a word that is zero when the lock is available and non-zero when it is held.Logically, xv6 should acquire a lock by executing code like

21 void

22 acquire(struct spinlock *lk)

23 {

24 for(;;) {

25 if(!lk->locked) {

26 lk->locked = 1;

27 break;

28 }

29 }

30 }

Unfortunately, this implementation does not guarantee mutual exclusion on a modernmultiprocessor. It could happen that two (or more) CPUs simultaneously reach line25, see that lk->locked is zero, and then both grab the lock by executing lines 26 and27. At this point, two different CPUs hold the lock, which violates the mutual exclusion property. Rather than helping us avoid race conditions, this implementation ofacquire has its own race condition. The problem here is that lines 25 and 26 executed as separate actions. In order for the routine above to be correct, lines 25 and 26must execute in one atomic (i.e., indivisible) step.

To execute those two lines atomically, xv6 relies on a special 386 hardware instruction, xchg (0569). In one atomic operation, xchg swaps a word in memory withthe contents of a register. The function acquire (1474) repeats this xchg instruction ina loop; each iteration reads lk->locked and atomically sets it to 1 (1483). If the lock isheld, lk->locked will already be 1, so the xchg returns 1 and the loop continues. Ifthe xchg returns 0, however, acquire has successfully acquired the lock—locked was0 and is now 1—so the loop can stop. Once the lock is acquired, acquire records, fordebugging, the CPU and stack trace that acquired the lock. When a process acquires alock and forget to release it, this information can help to identify the culprit. Thesedebugging fields are protected by the lock and must only be edited while holding thelock.

The function release (1502) is the opposite of acquire: it clears the debuggingfields and then releases the lock.

Modularity and recursive locks¶

System design strives for clean, modular abstractions: it is best when a caller doesnot need to know how a callee implements particular functionality. Locks interferewith this modularity. For example, if a CPU holds a particular lock, it cannot call anyfunction f that will try to reacquire that lock: since the caller can’t release the lock until f returns, if f tries to acquire the same lock, it will spin forever, or deadlock.

There are no transparent solutions that allow the caller and callee to hide whichlocks they use. One common, transparent, but unsatisfactory solution is recursivelocks, which allow a callee to reacquire a lock already held by its caller. The problemwith this solution is that recursive locks can’t be used to protect invariants. After insert called acquire(&listlock) above, it can assume that no other function holdsthe lock, that no other function is in the middle of a list operation, and most importantly that all the list invariants hold. In a system with recursive locks, insert can assume nothing after it calls acquire: perhaps acquire succeeded only because one ofinsert’s caller already held the lock and was in the middle of editing the list datastructure. Maybe the invariants hold or maybe they don’t. The list no longer protectsthem. Locks are just as important for protecting callers and callees from each other asthey are for protecting different CPUs from each other; recursive locks give up thatproperty.

Since there is no ideal transparent solution, we must consider locks part of thefunction’s specification. The programmer must arrange that function doesn’t invoke afunction f while holding a lock that f needs. Locks force themselves into our abstractions.

Code: Using locks¶

Xv6 is carefully programmed with locks to avoid race conditions. A simple example isin the IDE driver (3800). As mentioned in the beginning of the chapter, iderw (3954)has a queue of disk requests and processors may add new requests to the list concurrently (3969). To protect this list and other invariants in the driver, iderw acquires the idelock (3965) and releases at the end of the function. Exercise 1 explores how to trigger the race condition that we saw at the beginning of the chapter by moving the acquire to after the queue manipulation. It is worthwhile to try the exercise because itwill make clear that it is not that easy to trigger the race, suggesting that it is difficultto find race-conditions bugs. It is not unlikely that xv6 has some races.

A hard part about using locks is deciding how many locks to use and which dataand invariants each lock protects. There are a few basic principles. First, any time avariable can be written by one CPU at the same time that another CPU can read orwrite it, a lock should be introduced to keep the two operations from overlapping.Second, remember that locks protect invariants: if an invariant involves multiple datastructures, typically all of the structures need to be protected by a single lock to ensurethe invariant is maintained.

The rules above say when locks are necessary but say nothing about when locksare unnecessary, and it is important for efficiency not to lock too much, because locksreduce parallelism. If efficiency wasn’t important, then one could use a uniprocessorcomputer and no worry at all about locks. For protecting kernel data structures, itwould suffice to create a single lock that must be acquired on entering the kernel andreleased on exiting the kernel. Many uniprocessor operating systems have been converted to run on multiprocessors using this approach, sometimes called a ‘‘giant kernellock,’’ but the approach sacrifices true concurrency: only one CPU can execute in thekernel at a time. If the kernel does any heavy computation, it would be more efficientto use a larger set of more fine-grained locks, so that the kernel could execute on multiple CPUs simultaneously.

Ultimately, the choice of lock granularity is an exercise in parallel programming.Xv6 uses a few coarse data-structure specific locks; for example, xv6 uses a single lockprotecting the process table and its invariants, which are described in Chapter 5. Amore fine-grained approach would be to have a lock per entry in the process table sothat threads working on different entries in the process table can proceed in parallel.However, it complicates operations that have invariants over the whole process table,since they might have to take out several locks. Hopefully, the examples of xv6 willhelp convey how to use locks.

Lock ordering¶

If a code path through the kernel must take out several locks, it is important that allcode paths acquire the locks in the same order. If they don’t, there is a risk of dead-lock. Let’s say two code paths in xv6 needs locks A and B, but code path 1 acquireslocks in the order A and B, and the other code acquires them in the order B and A.This situation can result in a deadlock, because code path 1 might acquire lock A andbefore it acquires lock B, code path 2 might acquire lock B. Now neither code path canproceed, because code path 1 needs lock B, which code path 2 holds, and code path 2needs lock A, which code path 1 holds. To avoid such deadlocks, all code paths mustacquire locks in the same order. Deadlock avoidance is another example illustratingwhy locks must be part of a function’s specification: the caller must invoke functionsin a consistent order so that the functions acquire locks in the same order.

Because xv6 uses coarse-grained locks and xv6 is simple, xv6 has few lock-orderchains. The longest chain is only two deep. For example, ideintr holds the ide lockwhile calling wakeup, which acquires the ptable lock. There are a number of otherexamples involving sleep and wakeup. These orderings come about because sleepand wakeup have a complicated invariant, as discussed in Chapter 5. In the file systemthere are a number of examples of chains of two because the file system must, for example, acquire a lock on a directory and the lock on a file in that directory to unlink afile from its parent directory correctly. Xv6 always acquires the locks in the order firstparent directory and then the file.

Interrupt handlers¶

Xv6 uses locks to protect interrupt handlers running on one CPU from non-interruptcode accessing the same data on another CPU. For example, the timer interrupt handler (3114) increments ticks but another CPU might be in sys_sleep at the sametime, using the variable (3473). The lock tickslock synchronizes access by the twoCPUs to the single variable.

Interrupts can cause concurrency even on a single processor: if interrupts are enabled, kernel code can be stopped at any moment to run an interrupt handler instead.Suppose iderw held the idelock and then got interrupted to run ideintr. Ideintrwould try to lock idelock, see it was held, and wait for it to be released. In this situation, idelock will never be released—only iderw can release it, and iderw will notcontinue running until ideintr returns—so the processor, and eventually the wholesystem, will deadlock.

To avoid this situation, if a lock is used by an interrupt handler, a processor mustnever hold that lock with interrupts enabled. Xv6 is more conservative: it never holdsany lock with interrupts enabled. It uses pushcli (1555) and popcli (1566) to manage astack of ‘‘disable interrupts’’ operations (cli is the x86 instruction that disables interrupts. Acquire calls pushcli before trying to acquire a lock (1476), and release callspopcli after releasing the lock (1521). Pushcli (1555) and popcli (1566) are more thanjust wrappers around cli and sti: they are counted, so that it takes two calls to popcli to undo two calls to pushcli; this way, if code acquires two different locks, interrupts will not be reenabled until both locks have been released.

It is important that acquire call pushcli before the xchg that might acquire thelock (1483). If the two were reversed, there would be a few instruction cycles when thelock was held with interrupts enabled, and an unfortunately timed interrupt woulddeadlock the system. Similarly, it is important that release call popcli only after thexchg that releases the lock (1483).

The interaction between interrupt handlers and non-interrupt code provides anice example why recursive locks are problematic. If xv6 used recursive locks (a second acquire on a CPU is allowed if the first acquire happened on that CPU too), theninterrupt handlers could run while non-interrupt code is in a critical section. Thiscould create havoc, since when the interrupt handler runs, invariants that the handlerrelies on might be temporarily violated. For example, ideintr (3902) assumes that thelinked list with outstanding requests is well-formed. If xv6 would have used recursive locks, then ideintr might run while iderw is in the middle of manipulating thelinked list, and the linked list will end up in an incorrect state.

Memory ordering¶

This chapter has assumed that processors start and complete instructions in theorder in which they appear in the program. Many processors, however, execute instructions out of order to achieve higher performance. If an instruction takes manycycles to complete, a processor may want to issue the instruction early so that it canoverlap with other instructions and avoid processor stalls. For example, a processormay notice that in a serial sequence of instruction A and B are not dependent on eachother and start instruction B before A so that it will be completed when the processorcompletes A. Concurrency, however, may expose this reordering to software, whichlead to incorrect behavior.

For example, one might wonder what happens if release just assigned 0 to lk->locked, instead of using xchg. The answer to this question is unclear, because differ-ent generations of x86 processors make different guarantees about memory ordering.If lk->locked=0, were allowed to be reordered say after popcli, than acquire mightbreak, because to another thread interrupts would be enabled before a lock is released.To avoid relying on unclear processor specifications about memory ordering, xv6 takesno risk and uses xchg, which processors must guarantee not to reorder.

Real world¶

Concurrency primitives and parallel programming are active areas of of research, because programming with locks is still challenging. It is best to use locks as the basefor higher-level constructs like synchronized queues, although xv6 does not do this. Ifyou program with locks, it is wise to use a tool that attempts to identify race conditions, because it is easy to miss an invariant that requires a lock.

User-level programs need locks too, but in xv6 applications have one thread of execution and processes don’t share memory, and so there is no need for locks in xv6applications.

It is possible to implement locks without atomic instructions, but it is expensive,and most operating systems use atomic instructions.

Atomic instructions are not free either when a lock is contented. If one processorhas a lock cached in its local cache, and another processor must acquire the lock, thenthe atomic instruction to update the line that holds the lock must move the line fromthe one processor’s cache to the other processor’s cache, and perhaps invalidate anyother copies of the cache line. Fetching a cache line from another processor’s cachecan be orders of magnitude more expensive than fetching a line from a local cache.

To avoid the expenses associated with locks, many operating systems use lock-freedata structures and algorithms, and try to avoid atomic operations in those algorithms.For example, it is possible to implemented a link list like the one in the beginning ofthe chapter that requires no locks during list searches, and one atomic instruction toinsert an item in a list.

Exercises¶

- get rid off the xchg in acquire. explain what happens when you run xv6?

- move the acquire in iderw to before sleep. is there a race? why don’t you observe itwhen booting xv6 and run stressfs? increase critical section with a dummy loop; whatdo you see now? explain.

- do posted homework question.

- Setting a bit in a buffer’s flags is not an atomic operation: the processor makes acopy of flags in a register, edits the register, and writes it back. Thus it is importantthat two processes are not writing to flags at the same time. xv6 edits the B_BUSY bitonly while holding buflock but edits the B_VALID and B_WRITE flags without holdingany locks. Why is this safe?